Dallas ABC affiliate station WFAA is reporting on deaths in for-profit jails run by LaSalle Corrections. The story includes information on the case of Michael Sabbie and features an interview of Erik Heipt, one of the attorneys for the Sabbie family:

Jailed to death: False paperwork, deaths widespread in N. Texas for-profit’s jails

About a week before she turned 21, Morgan Angerbauer, a diabetic, died of a severe lack of insulin on the floor of a cell in the Bi-State Jail in Texarkana. Jailers and a nurse ignored her as she screamed for help for hours in 2016, records show.

A year earlier in the same Bowie County jail, Michael Sabbie, also a diabetic with asthma and heart problems, repeatedly told nurses he was having trouble breathing. Guards pepper sprayed him as he screamed, “I can’t breathe.” Sabbie, 35, was found dead of a heart attack on his cell floor.

Also in 2015, this time in Johnson County’s jail, Ronald Ray Beesley died from an infection after repeatedly telling jail medical staff he couldn’t breathe and had chest pains.

Their families, and their attorneys, say LaSalle Corrections – which runs both the Bowie and Johnson county jails – ignored their loved one’s pleas for medical attention.

LaSalle is a private Louisiana-based, for-profit company that makes money taking care of inmates for counties and the federal government. They run local jails all over Texas and Louisiana.

A nine-month WFAA investigation found serious problems at four of LaSalle’s northern Texas lock-ups: Johnson, Parker, Bowie and McLennan counties. News 8 found that jail medical staff repeatedly violated the company’s policies, and jailers falsified records claiming they had checked on Sabbie, Angerbauer and three other inmates who died in LaSalle’s jails in Waco and Weatherford.

“LaSalle Corrections is not a good operator,” said Lance Lowry, an expert on the Texas prison industry and former president of the Texas Correctional Employees union. “This is a company that puts profit over human lives.”

LaSalle did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. The company has denied wrongdoing in response to lawsuits filed by the families of Sabbie, Angerbauer and Beesley.

“He knows he’s in heaven”

Beesley’s namesake was just 16 months old when his dad died at 46.

“He still tells me, ‘Is my daddy coming to get me?'” said his mother, Kristi White. “And I have to tell him, ‘no.’ He knows he’s in heaven.”

The events that culminated in Beesley’s death began on May 12, 2015.

Beesley flipped his pickup in a drunk-driving crash in Cleburne. At the time of his arrest, it was clear that Beesley was in pain. In police videos, he repeatedly clutched his chest and complained of severe pain.

Not realizing the severity of his injuries, he did not seek medical treatment. He was released from the Johnson County jail on bail.

Two weeks later, he turned himself in at the same jail on May 25, 2015, for a parole violation resulting from the DWI accident.

In that jail, run by LaSalle, Beesley told the medical staff that his chest hurt and he had been in a rollover accident. He would tell them that he thought he had “rib or sternum injuries.”

Beesley’s family grew worried, too.

His wife visited him the day before he died.

She said he could barely walk, and that his hand was so swollen he couldn’t hold the phone. He could hardly talk, she said. He told her to get help.

“It was bad,” White said. “I’ve never seen him like that.”

The last thing he managed to tell her was that he didn’t want her to come back to the jail. He didn’t want her to see him in such bad shape.

She talked to a jail lieutenant, telling him she thought her husband was dying. “He’s like, ‘Ma’am, you don’t know that,’” White recalled him saying.

In tears, White called her sister-in-law, Patricia Ford. She, too, called the jail lieutenant.

“I said to him ‘Sir, my brother is dying.’ He said ‘Ma’am you don’t know that’s what’s going on,'” Ford said. “And I said ‘And you don’t know that it’s not.'”

No one from the medical staff examined Beesley that night, according to jail medical records.

The next day, he was examined by three members of the jail’s medical staff. Tests were conducted, but the lab results took time to process.

That night, a jailer found Beesley on the floor of his cell. He could not stand on his own, according to a report by the Texas Rangers, who investigated the death. Beesley became unresponsive. He was later pronounced dead at a Cleburne hospital.

Beesley was dead before anyone saw the lab tests. Those labs indicated that Beesley’s sodium levels were critically low – evidence of a serious medical issue.

“For seven days, he suffered until he died,” said Ford, Beesley’s sister. “We’re talking antibiotics, is all he needed.”

She’s right. An autopsy showed that he died from “infectious complications” resulting from a “sternal fracture” from his pickup crash.

“Is the criminal justice system really about making money?” Ford said. “It should be more than about just making money.”

Emil Lippe, the family’s attorney, says the company cuts corners and it’s costing people’s their lives.

“They treat the inmates as if they’re not people,” he said. “It’s just a callous attitude.”

Deadly refusal to help

Jennifer Houser says her young daughter, Morgan Angerbauer, was dynamite in small package.

Morgan, a thin wisp of a girl, wasn’t even five feet tall. She tended to change her hair color with her moods, her mother recalled.

“She was a lively girl, full of spunk,” she said.

Morgan, like many teens, experimented with drugs. She became addicted.

On June 28, 2016, Morgan ended up in LaSalle’s Bi-State Jail in Bowie County for violating her probation on an earlier drug charge.

Morgan was diabetic and would die without insulin. That’s exactly what happened to her.

On the afternoon of June 30, Morgan refused to allow staff to check her blood sugar, according to police records.

About an hour later, Morgan told jail nurse Brittany Johnson that she was ready to have it checked. Johnson refused.

“I told her ‘no’ because that is not how it works,” Johnson told Texarkana police investigators.

In explaining her decision-making, Johnson said she was predisposed to believe that prisoners were lying.

A LaSalle jail sergeant told police detectives he heard Morgan screaming “at the top of her lungs” for hours in her cell. He said he ignored the screams.

“I should have went over and checked on her,” he later said.

About 4 a.m. on July 1, 2016 – almost 12 hours later – a jail trusty noticed Morgan unconscious on the floor of her cell. By then, almost 24 hours had elapsed since someone gave her insulin, and more than 17 hours since someone checked her blood sugar.

But, according to an arrest warrant affidavit, Johnson initially believed Morgan was pretending to be unconscious. She told Morgan that “she knew she was acting,” documents show.

Johnson tried repeatedly to get a fingerstick blood glucose level. She kept getting error messages.

All Morgan needed was insulin.

Inexplicably, though, the nurse “went and got some glucose (sugar) and gave it her to see if she would respond,” documents show.

More than 40 minutes elapsed before the nurse started CPR and EMS was called, according to state nursing board records.

Morgan’s final moments

Jail videos show the final moments of Morgan’s young life.

Her face is ashen as she lays on her cell floor. She murmurs unintelligibly. Johnson cuts off Morgan’s shirt and tries to resuscitate her using a portable defibrillator. It doesn’t work.

Morgan dies sprawled out on the floor, laying in vomit. Jailers cover her body with an orange blanket.

“She looked like a little rag doll,” said former LaSalle jailer Mason Cleghorn, who saw it all and agreed to talk to WFAA.

He said he kept telling the nurse that Morgan needed to go the hospital. But the nurse, he said, kept saying no.

“‘She’s not getting out like that,'” he recalled her saying.

An autopsy found Morgan died of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Her sugar level was 813 – more than five times the normal range. No illegal drugs were found in her system.

“Things could have went differently,” Cleghorn said. “A lot differently.”

He quit his job with LaSalle about a month after Morgan died.

Cleghorn agreed to talk at the request of Morgan’s mom. The two became friends since Morgan died.

“In my opinion, they’re in it for the money,” he said. “They don’t really care too much about the inmates.”

Johnson, the nurse, pleaded guilty to misdemeanor negligent homicide.

“She basically let Morgan die,” her mother said, crying.

More neglect

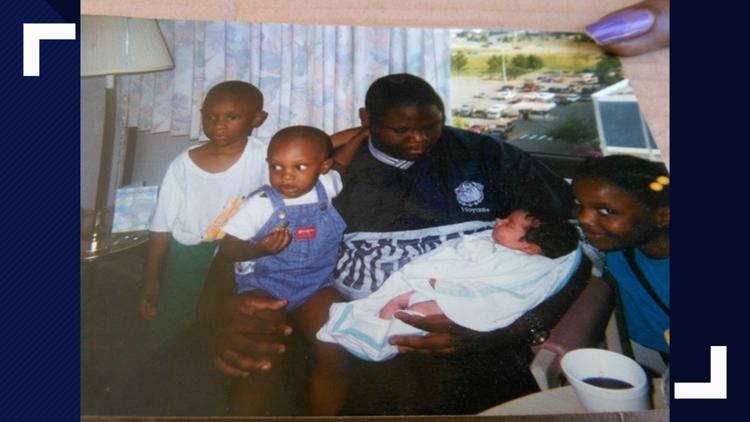

A year earlier, Michael Sabbie was booked into the same Bi-State Jail in Bowie County on a misdemeanor verbal assault charge on July 19, 2015.

Sabbie told the medical staff he had heart problems, diabetes and asthma. He also said he needed a diabetic diet.

Sabbie’s blood pressure and insulin levels were to be checked daily. That did not happen, nor was he given medication for any of his medical conditions, jail medical records show.

Former LaSalle nurses testified in depositions that they either didn’t know certain medical protocols existed, or didn’t think they had to follow them.

In the early morning hours of July 20, he told a nurse he was having trouble breathing while laying down – a symptom of impending heart failure.

The nurse also said she did not know she was supposed to check his vital signs. “I should have taken vitals,” she testified. “I did not know it was against policy.”

On July 21, around mid-morning, a cellmate found Sabbie collapsed on the floor. Guards brought him to the medical staff in a wheelchair. He told them that he couldn’t breathe. That nurse did not take Sabbie’s blood pressure or test his blood sugar levels.

A guard, however, cited Sabbie. He wrote that Sabbie had created a disturbance “by feigning illness and difficulty breathing.”

That afternoon, Sabbie appeared in court. The judge and other court personnel noticed that he was in medical distress.

He told the judge had he needed to go the hospital, and that he had been spitting up blood, according to a lawsuit his family later filed. But that did not happen. Instead, he was taken back to LaSalle’s jail.

“I can’t breathe”

Jail videos, obtained by WFAA, document Sabbie’s slow slide toward death.

The video shows him struggling to stand, leaning against a wall. His hands on are his knees, and he appears to be struggling to catch his breath.

A jailer approaches when Sabbie tries to walk toward the booking area. He grabs Sabbie by the shirt and throws him to the ground.

Several guards pile on top of him, and he is handcuffed. A jail lieutenant sprays Sabbie, who has asthma, in the face with pepper spray.

“I can’t breathe,” he says. “I can’t breathe.”

Sabbie repeats this like a prayer as he gasps for air.

The guards pull him off the floor. As Sabbie staggers, his pants fall down; no one helps the man cover himself. He’s taken to the nurse’s station.

“You better quit resisting,” a guard tells him.

“I can’t breathe,” the inmate says.

The nurse examines him for less than a minute. She does not check his blood pressure or his blood sugar levels, records show.

The video then shows LaSalle guards walking Sabbie to the showers. “If you don’t comply with orders, gas will be administered to you again,” a guard tells him.

“I can’t breathe,” Sabbie says, still gasping. He can barely stand up as they turn on the water. “Stay back in the shower,” a guard yells at him.

“I’m sorry,” the dying inmate says.

He then falls to the wet floor.

Guards pick him up and escort a gasping Sabbie to a cell.

“Keep still,” one tells him as they, one by one, walk out and shut the door.

With the video still rolling, one guard asks, through a small glass window, if Sabbie wants to make a statement.

They leave Sabbie sprawled out in wet clothes on the concrete.

He lays there for about 12 hours. On the morning of July 22, jailers discovered Sabbie dead. An autopsy found that he died of a heart attack.

“Deliberate indifference”

“It showed a deliberate indifference to human life,” said Erik Heipt, a Seattle-based attorney who represents Sabbie’s widow. “There was plenty of time to get help for Michael Sabbie.”

Under state regulations, jailers are supposed to check on inmates who are in a segregation cell every half hour. A LaSalle jailer filled out records indicating she checked on Sabbie throughout her 12-hour shift. During a deposition later, she admitted she only did a few of them. None resulted in additional treatment for him.

The jailer later testified that her sergeant told her to leave Sabbie alone. Several times that night, she said she looked in the cell and saw Sabbie lying on the ground. His pants were still pulled down and his genitals were showing.

The jailer testified she thought she saw his chest moving. “I’m like, ‘Okay, he’s breathing, so he’s alive,'” she testified.

She testified she had been working for LaSalle for about three weeks when Sabbie died. She testified she was trained to fill out paperwork saying security checks were done, even if they were not.

She said it was a widespread practice.

Records show jailers also falsified security checks in Morgan Angerbauer’s case, too.

Like Sabbie, jailers were required to check her every 30 minutes.

An internal LaSalle review showed a jailer did not check on her for nine hours. He falsified logs indicating he had done so, according to the review. Another jailer claimed he completed checks over a four-hour period, but in fact, only did one.

One of the jailers who was supposed to check on Angerbauer said he fell behind on the checks “due to lack of staff,” according to his statement to investigators.

More falsified checks

Falsified jail checks also played role in three additional death at LaSalle’s jails in Waco and another in Parker County west of Dallas.

Michael Martinez

On Nov. 1, 2015, Martinez was found hanging from the ceiling of his cell at the Jack Harwell Detention Center in Waco, according to McLennan County Sheriff’s investigation records.

The investigation found no one checked on Martinez for three hours. Jailers were required to check on him every 30 minutes.

Three guards were charged with tampering with governmental documents.

One jailer told investigators that he did not check on Martinez as required “because he was working by himself” in that wing of the jail.

Kristian Culver

Seven months later, in May 2016, Culver was also an inmate at the Harwell Detention Center in Waco. He hung himself with braided pieces of a bed sheet. He was supposed to be checked on every 30 minutes.

Jail surveillance showed he was not checked on for more than two hours, according to a Texas Rangers’ investigative report.

In a statement to investigators, a jailer said the “shift was extremely shorthanded so he was pulled from his area of responsibility and tasked to conduct other duties throughout the detention center.” He said he told a supervisor that he needed help, but help wasn’t provided.

He said a supervisor told him he was not allowed to “leave work until the log looked right.” He took it to mean “he had to back-fill the times and make it looked like he conducted the rounds.”

A grand jury later declined to indict him.

Denay Lauren Birnie

On Nov. 9, 2017, in Weatherford, Birnie was found dead in LaSalle’s Parker County jail. A Texas Rangers investigative report said falsified jail checks played a role in her death as well.

Birnie had been arrested on a felony driving while intoxicated charge. She was placed in a holding cell with several other women. She was later found unresponsive and died at a local hospital. An autopsy found Birnie died of a methamphetamine overdose.

A former Lasalle jail sergeant told a Texas Ranger that he had written that that he had done the security checks, but he really hadn’t. He said he never did look in the holding cell because they were shorthanded and he got busy.

He, too, said it was common practice to falsify checks.

“Cause for grave concern”

Two of LaSalle’s jails failed inspections this year over, among other things, falsified jail checks.

In June, the Johnson County Jail failed its inspection. In August, LaSalle’s Harwell facility in Waco also failed an inspection. It was that jail’s third failure in four years.

“Situations like that, those are cause for grave concern,” said Brandon Wood, executive director of the Texas Commission on Jail Standards.

Jail checks are critical to safety and are a “basic tenant of jail operations,” he said.

Wood said LaSalle and some of their facilities have had “continual noncompliance issues.” He also said LaSalle had seemed to have more noncompliance issues than The Geo Group, the other for-profit company that operates county jails in Texas.

In a statement, Johnson County Sheriff Adam King pointed out that no deaths had occurred since he became sheriff in January 2017. He said he was “unaware of any serious or major issues that would justify” asking county commissioners to end their contract with LaSalle.

The sheriff that oversees the LaSalle’s Bi-State Jail where Sabbie and Beesley died did not respond to a request for comment. The sheriffs in McLennan and Parker counties also did not respond.

Again, LaSalle has ignored WFAA’s repeated requests for an interview.

“Anywhere they can cut corners to maximize profits, they will,” said Lance Lowry, the prison industry expert. “It’s all about maximizing the profits.”

Meanwhile, the families of those who died in LaSalle facilities continue to deal with the loss.

“That little boy could still have his daddy,” Kristi Wright said of her and Ronald Beesley’s toddler son.

Jennifer Houser, Morgan Angerbauer’s mother, said she had a message for LaSalle’s leadership.

“How do you sleep at night?” she said. “These inmates, they’re not human – they’re a dollar sign for you. How would you feel if that was your family?”