WFAA Dallas is reporting on the death of Holly Barlow-Austin, following her confinement in a Texarakana jail run by LaSalle Corrections. Budge & Heipt represent members of Ms. Barlow-Austin’s family.

From FAA Dallas, December 18, 2019:

She got critically ill in a jail run by a for-profit company. She died, but there was no criminal investigation. Why?

TEXARKANA, Texas — By the time jailers at the Bi-State Jail in Texarkana sent Holly Austin to the hospital this past June, she was “blind” and “unable” to even sign her name on the admission paperwork.

She was in severe pain, disoriented, couldn’t walk and “unable to hold objects in her hands,” according to hospital records obtained by WFAA.

As Holly lay near death, the sheriff suddenly ordered her released from custody. The result? When Austin did die soon after, the private, for-profit company that operates the jail was not required to report her death to state officials nor was her death criminally investigated.

A WFAA investigation found the company, LaSalle Corrections, taking advantage of a loophole that allows jails to avoid criminal investigations into the deaths of some prisoners who become critically ill while in custody. The loophole allows authorities to release a prisoner, and then when they die, there is no requirement that a criminal investigation be conducted or that potential evidence be preserved.

Austin’s family, as well as jail watchdogs, say the loophole allows jails to hide cases of medical neglect and avoid accountability.

“They didn’t want to be responsible for her death,” said her mother, Mary Mathis, of Texarkana. “Once she started going downhill, they should have done something, but they basically ignored it.”

WFAA reported Austin’s death to the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, prompting state regulators to launch their own investigation. The commission is authorized to investigate whether state jail standards have been violated, but cannot conduct criminal investigations. State jail regulators found that the medical care provided to Austin did not “meet minimum jail standards,” according to records obtained by WFAA.

Both LaSalle officials and the Bowie County Sheriff James Prince declined to answer questions.

For more than a year, WFAA has been investigating the way LaSalle runs its county jails in Texas. Investigations repeatedly have shown that the for-profit company’s guards and staff failed to give appropriate medical treatment to people who get sick while locked up in their jails.

WFAA’s investigation resulted in LaSalle officials being grilled by lawmakers this past spring. Because of our reporting, state lawmakers closed another loophole that allowed county jailers to be on the job for up to a year with virtually no training. Lawmakers also imposed new requirements on private companies operating county jails.

But Holly Austin’s family says her death exposes another gap in the law that they want fixed.

Holly’s story

Austin’s family said she battled an addiction to drugs for years before recently deciding to seek help.

While on probation in Texarkana for a misdemeanor, she cut off her ankle monitor and traveled 175 miles away to attend a drug treatment program in Dallas. When she returned to Texarkana, she had to face the consequences.

Austin was booked into the Bi-State jail on April 5.

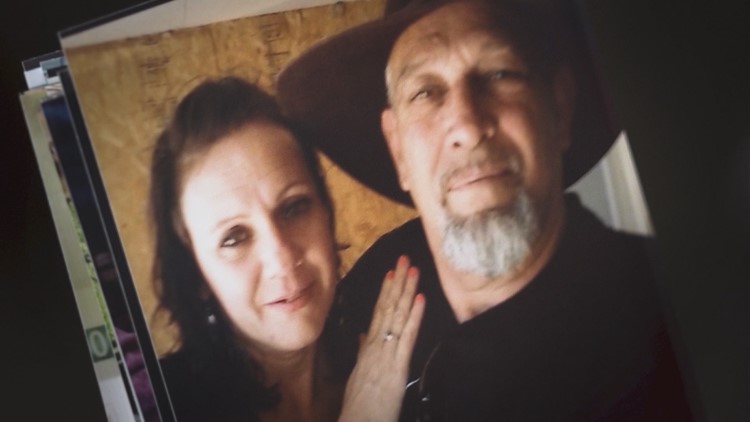

“She told me when she got home, ‘I’m going to be the wife that you really deserve,’” said Mike Austin, her husband of four years.

His wife suffered from a life-threatening autoimmune condition. She needed to take an expensive drug to keep her alive. Her husband took nearly a month’s supply to the jail, assuming the staff there would give it to her.

As the weeks passed, Austin got sick, her husband said. She complained she had a headache and that her legs hurt.

“It got to where they’d bring her in a wheelchair,” he said. “She couldn’t walk on her own.”

He said his wife told him she thought jailers were messing up her medications. Her husband called the jail’s medical unit and tried to talk to them, but they would not discuss her condition with him.

The last time her husband saw her, it was a brief visit. She was sick and wanted to lay down, he said.

“She told me ‘Baby, when I get out of here, I’ll be able to get well and we’ll be happy,’” he said.

But when he tried to visit the next couple of times, jailers told him his wife was refusing to see him. He said he suspects she was too ill to get out of bed.

Her mother, Mary Mathis, also said jailers told her that her daughter refused to see her. Mathis said her daughter also didn’t respond to messages via the jail computer system, either.

Elizabeth Edwards was locked up in Texarkana at the same time as Holly Austin. She told WFAA that Austin was very sick. She also said guards accused her of faking.

“The guards wouldn’t do nothing,” Edwards told WFAA. “She was begging for help. She would ask them please take me to the hospital.”

She said she and other inmates had to assist Austin. She said that, at one point, Austin was put in a holding area and left lying on the floor.

“She couldn’t sit up anymore,” Edwards said. “We used to watch the guards snicker and laugh about it. It was obvious she was not faking.”

Records show Holly filled out five medical requests between April 13 and May 29. She was “dizzy,” didn’t have an appetite, suffered from an “extreme headache” and was “unable to stand,” the records show.

At the hospital

On June 11, Austin was admitted to a Texarkana hospital in critical condition, records show.

“She is awake but unable to tell her status,” an emergency room doctor wrote in her chart.

Hospital officials were told that she’d been exhibiting “an altered mental status for several days” and had been “refusing treatment in the jail for weeks,” according to hospital records.

Doctors would soon find she had meningitis and began treating her for it. Her condition never improved.

But for four days, her family had no idea she was fighting for her life in a hospital bed.

On the morning of Saturday, June 15, Mike Austin again tried to see his wife. This time, he was told she wasn’t in the jail.

“I said, ‘Well, where is she?’” he said.

Jailers told him they could not say. Mike Austin said he and Bowie County Sheriff James Prince have known each other for decades, so he called him for help. The sheriff told him she had been in the hospital for days. Austin said the sheriff told him he couldn’t get the family in to see her until that Monday, June 17.

In desperation, Mathis sent the sheriff a Facebook message begging for permission to see her daughter immediately. Finally, the family said, the sheriff interceded with LaSalle, and the family finally saw her about midday on June 15. When they got to the hospital room, a LaSalle guard was standing watch at the intensive care unit.

Austin was unresponsive. She couldn’t speak.

“She tried to raise her hand one time,” her husband said, his voice quivering.

Austin’s sister, Andrea Mathis, is a nurse. She told WFAA that she told the guard that she didn’t think her sister was going to live. The guard soon left the room. A few hours later, a LaSalle official showed up asking the family to sign the patient’s name on release paperwork because she was too sick to write.

The paperwork shows Austin was being released for “medical reasons,” per the sheriff. She was formally released at 3:36 p.m. on June 15.

About 10 hours later, with her husband at her bedside, Holly Austin’s heart stopped beating and she quit breathing. Doctors revived her and put her on a ventilator. Tests showed that there was no blood flow to the brain which was “consistent with brain death,” hospital records show.

“It was hard just looking at her laying there with no response,” her mother said. “We’d talk to her, tell her we loved her.”

Family members gathered around her bed as she was pronounced dead at 12:28 p.m. on June 17. She was 47.

Sepsis was listed on her death certificate as Austin’s primary cause of death, with meningitis listed as a secondary cause.

“I feel in my heart she held on until we got there,” her husband said. “If I could have, I’d have crawled up on that bed and took her place. That’s just how much I loved her.”

No investigation

Because Holly Austin had been “released” from LaSalle’s custody shortly before she died, her death was not reported to the state, and no criminal investigation was conducted.

WFAA’s investigation found that this is not the first time LaSalle used this loophole.

Ivan Earl Allen was a prisoner in LaSalle’s Johnson County jail in 2011. He was booked for violating his probation in a DWI case.

Jail records show that he also repeatedly requested medical assistance. Jailers found him collapsed on his jail cell floor. Within hours of being sent to the hospital, a judge ordered that Allen be released from custody. He had sepsis, kidney failure, pneumonia and had gone into cardiac arrest, hospital records show.

Allen died four days later. He was 69.

Just like Holly Austin, his death was not criminally investigated because he was no longer a prisoner when he died. LaSalle later settled a lawsuit with his family.

“It’s shameful that jails can ship someone to a hospital and then the person is bonded out so that they don’t’ show up as a death in custody on the records,” Diana Claitor of the Texas Jail Project, a nonprofit that monitors county jails.

On June 28, WFAA reported Austin’s death to the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, which oversees county jails. A commission inspector found Austin’s “medications were not dispensed as prescribed” and that the jail did not document when a family member brought Holly Austin’s medications to the jail, according to state records.

“The name and type of medication was not noted or recorded in the medical records and could not be verified for dispensing,” the records note.

The investigation further found that Austin’s medications did not follow her when she was moved from the main county jail to an annex jail facility. The records found that jail medication logs noted that Austin had not received medications on two specific days. When asked what happened, jail officials replied that they did not know why it had occurred, according to commission records.

“What happened to Holly was unconscionable,” said the family’s attorney, Erik Heipt. “LaSalle kept her locked up until she was at death’s door—when it was too late to save her life. The lack of humanity exhibited during her confinement is breathtaking.”

Regulators want answers

Last month, LaSalle officials were forced to appear before the jail commission as a result of a new law that requires private jail operators to appear before the jail commission whenever they fail an inspection. The requirement was put in place as a result of WFAA’s investigation of LaSalle’s practices.

LaSalle’s Bowie County jail has failed its most recent annual inspection, the two prior annual inspections and four special inspections since 2015.

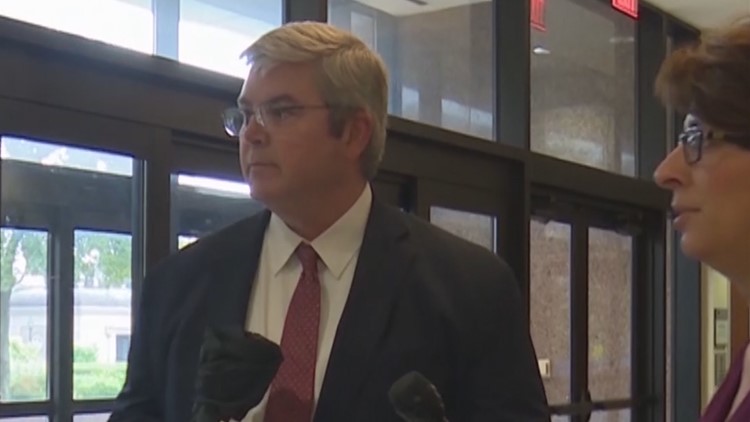

During that meeting, Jay Eason, LaSalle’s director of operations, told commissioners that the jail’s nursing staffed failed to document that Austin’s family brought her medication to the jail. He said that when Austin was moved to the jail annex, the medications did not follow her as they should have.

Eason told commissioners the facility’s nursing staff had been retrained, a medication verification form had been created and a new process started to ensure that medications follow an inmate when they are moved to a new facility. He also said that he planned to make it clear to the jail’s nursing staff that this is a “serious issue.”

After the meeting, Eason declined to comment, saying, “I can’t comment on that death in custody.” He refused to answer questions about whether there was a delay in taking Holly Austin to the hospital.

Sheriff James Prince was also at that commission meeting, and also declined to answer our questions, including why he ordered Austin’s release from custody as she lay near death in the hospital and whether it was an effort to avoid a criminal investigation should she die.

“Have a good day, ma’am,” he said, walking away.

Austin’s is just the latest death connected to the Bowie County jail. In 2016, 20-year-old Morgan Angerbauer died of a severe lack of insulin on the floor of a cell. Jailers and a nurse ignored her as she screamed for help for hours. A nurse was convicted for her role in Angerbauer’s death. A year earlier, Michael Sabbie, also a diabetic with asthma and heart problems, repeatedly told nurses he was having trouble breathing. Guards pepper-sprayed him as he screamed, “I can’t breathe.” Sabbie, 35, was found dead of a heart attack on his cell floor.

“It’s shocking that something like this could happen in the Bi-State Jail after the death of Michael Sabbie and after the death of Morgan Angerbauer,” said Heipt, who represented Sabbie’s family in a now-settled lawsuit for an undisclosed amount. “At this point, I can’t help but wonder how many deaths it will take before LaSalle gets the message that it needs to stop putting profits over people’s lives.”

Austin’s family wants state lawmakers to change the law to ensure that deaths like hers are criminally investigated.

“I understand that people have to suffer consequences for the bad things they do,” Mike Austin said. “But when you’re on a misdemeanor, you have to give your life for a misdemeanor?”